The Art of Letting Go of Your Ego in the Design Process

“How do you deal with harsh criticism?”

“How do you gain respect and trust from clients - especially when they think they know better?”

“How do you work with your teammates effectively without getting pissed off when they ask you to move pixels?”

I was taken aback when I was first asked about them – maybe because I was going through it myself but never really brought it to the front of mind or paid much attention to it. These questions kept coming up at different places I got to speak at with the wider community over the span of Singapore Design Week 2018.

^ Addressing the fresh batch of Year 1 UX Design students at Republic Polytechnic

Demarcating floors with masking tape, hanging massive foam boards as wall dividers and building life size service counters using hundreds of cardboard boxes – was how I started my first day – was how I started my design career in Ong&Ong Experience Design Studio (OXD) architectural firm six years ago. I hit the ground running as I got roped into the prototyping phase of the design process. Building life size mock-ups of a service experience, slapping post-its, role-playing as a distraught customer, was the world of design I got exposed to. The famous double-diamond methodology was pretty much my ABCs.

^ Double-diamond framework

As I matured in the field and found my groove, I got more involved in design research — conducting interviews with stakeholders, understanding the ground, systems, mapping out user journeys and pain-points and all that. I was swimming in data and found a lot of joy decoding and making sense of things and coming up with insights and strategies — then translating them into holistic integrated design solutions.

Come to think of it — I wasn’t doing a lot of design but more of thinking of the design. Well I’m obviously not an architect, neither had the 3D rendering skills nor the kind of technical skills needed to design a full on life-sized physical space down to measurement. But I have found a knack in trying to understand what makes people tick.

In retrospect, my stint in OXD had an environment that didnt allow much room for my ego to grow or present itself in the first place. I was so involved in research, that the voices of the stakeholders and users occupied my mind most of the time. I was made aware and conscious that I was designing for people from the get go. I was learning about their story, their challenges, their dreams and aspirations — everything revolved around them. This is what human-centred design means right? It had little to do with me. The approach was always “How can I help make it better for you?”

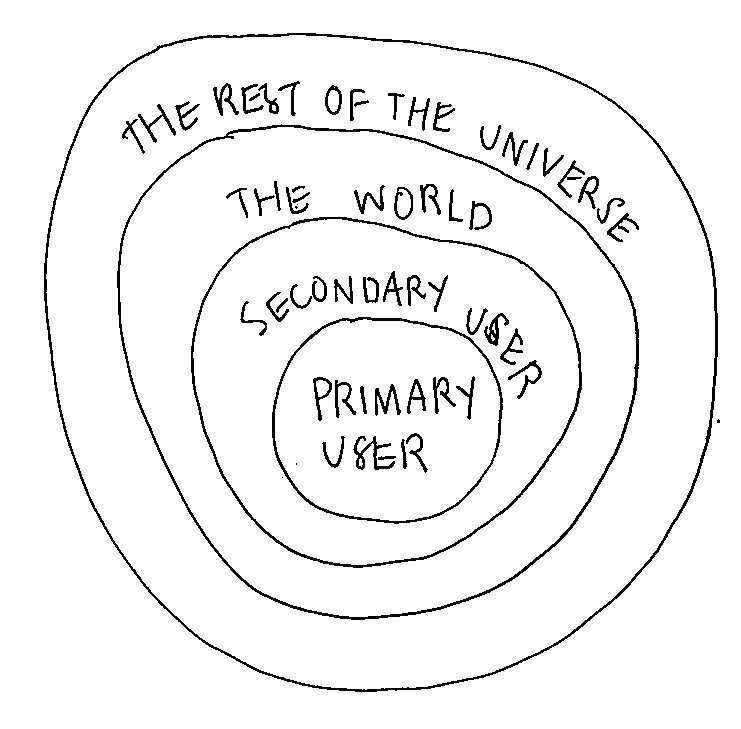

#1: Figure out who is at the centre of the universe

“Yeah well, it is easier said than done!”

Truth.

A couple of years in, I realise I wasn’t really playing the traditional role of a designer rather more of a design researcher/strategist. My deliverables were never fancy shiny design masterpiece — they were instead in the form of diagrams and insight reports that would later on help inform design decisions and strategy for the architect.

Fast forward to where I am now in Foolproof as a UX designer — my role has shifted. I am more involved towards the tail end of the design process. Specifically in doing the actual design — the execution. That in itself holds a different set of challenges and requires a specific kind of skill set. The start was absolutely frustrating. Especially when I not only switched roles — from being a design researcher to a designer — but also design fields — from designing physical space to now the digital space. Everything was seemingly new — new skills, new language, but oddly familiar.

What the heck is a hamburger??

I realised that it was the little things that frustrated me initially. It was all these small incremental changes, moving pixels to the left, making things bigger or smaller, italic, bold and what have you, that gets to me sometimes. I had to remind myself to be objective about things and not take it personally. It dawned on me that these are all trivial matters and gives me all the more reason to let it slide and accept that it is after all part of the process! Right?

Let’s face it, the reality is when you’re at the tail end of the process and you are knee deep in the actual making and designing of things — you spend hours in front of your computer, not your stakeholders. Your mindset shifts into production mode, and you focus on your technical abilities as a designer in making things happen. In that moment, it all comes down to your technical ability and skill in execution. All those years in design school is now being put to the test in translating all the findings from research into something tangible. Oh that’s alot of pressure to put on yourself.

^ Sat down as a Portfolio Reviewer at Portfolio Clinic hosted by Design Singapore as part of Singapore Design Week 2018.

Your mind goes “What can I make with this tool”, “Maybe I can do this”, “I can make this bigger and that in red”, you go into this cycle of “I, I, I, I, I…” When you start to live in your mind, and spend too much time on your own — the chances of getting your ego hurt increases exponentially. Be aware of how much of yourself you put in your work. Having said that, it is so easy to lose sight of the users, remind yourself who you are designing for — be informed by your research and not purely just from what you think is right.

“I spent hours on this and you say this is sh*t?!”

#2: Get your stakeholders and team in the room and get involved

The gap between what is in your own head (expectations) and what has already been explicitly tried and tested (reality) should not be on two extreme ends of the world. The gap between expectations and reality is what my mentor would call it, zone of suffering. The wider the gap, the more you’re going to suffer. It is therefore imperative to align and manage expectations throughout the design process. Be it your own expectations or your stakeholders.

Have working sessions with them, produce low fidelity paper wireframes, sketch your ideas, test, refine and start getting buy-ins or not as early as possible. Reduce the probability of a major upset by giving visibility on the design decisions throughout the process.

There is no place for the Starchitect — you should not be tucked far away in a secret chamber hiding from the world whilst working on your grand masterpiece. That is a gamble my friend. If you find yourself there, and really don’t want to get upset or have your ego hurt, stop! Go connect and speak to your team and stakeholders, have quick check-ins or daily stand-ups. Get involved. Align and reduce the gap.

#3: To not be treated like a tool, stop behaving like one

Don’t be a technical workhorse. Don’t just move pixels, change a colour or size just because the client ask you to. Don’t ask why for the sake of asking or to outsmart/undermine your client and inflate your ego. Ask because you genuinely want to make it work. Understand their point of view, and provide with alternative solutions or suggestions and back it with research. Be brave to challenge the way they think and see things. They may not agree with all of your suggestions and may have differing views. But as a professional, weigh in with your knowledge and expertise. Be familiar with best practices and learn how to talk about your ideas and the thinking behind your designs. Remember that you were engaged not solely for your hands (technical abilities) but also for your brains (knowledge/experience).

^ Facilitated a Photoshop class with 13 year olds at Temasek Polytechnic

“Maybe you could change this to make it blue-er?”

You should be asking “What best works for the business and users?” and if no one knows, then test it. Don’t go down the rabbit hole of playing the guessing game, stop living in the head — bring it back out and place it in front of the stakeholders and users. If there are two strong opinions about design, bring those 2 versions and do an A/B testing with users. As an evidence-based experience design agency at Foolproof, our design decisions are driven by insights we get from research. In that process, we also learn to remove our own biasness.

“It is not about who is right or wrong, it is about what works best.”

#4: Everything is a working prototype - change is the only constant

Going into the design process with a mentality that things will change will help you tremendously too. A matter of fact, the stuff you design and deliver is going to phase out one day and will be replaced with a new version. So don’t be too attached to your designs rather be attached in solving the right problem. Which is why it is important to test your ideas. Draw it out, make low-fi wireframes, do what you need to do to get feedback. Don’t assume. Don’t jump into designing quickly — make sure you have done all the research and testing. This will ease your design and delivery process tremendously.

Fail early, fail fast they say.

Constantly learn to break your own work — play the devil advocate. Trash it out and break it. It will only help you understand your work better and arm you with all the answers to tough questions that might come your way. As the maker and creator of the design, you should know the loopholes, flaws and the work arounds. Come up with different versions and variations and play out different scenarios — make it bullet proof — make it Foolproof.

#5: Accept that you don’t have, and may never will, have all the answers — and that is absolutely, perfectly fine

It is impossible to achieve perfection, but close enough for most parts is good enough. Learning to design human experiences is never an easy feat, and I have come to learn the value of unpacking my own complexities to find relevance and build stronger empathy when designing for others. The first step was to recognize and accept my own limitations and imperfections. To learn to not write myself off and have confidence in my own abilities. There is a difference between being egoistic to being confident.

It was said to me once that “You are not your work. You are not your job.” I didn’t understand it at first but later figured out that I am not my work, because I am more than just my work. There is a lot more to what makes who you are and that is not usually defined by one single thing that you do. This is always a good reminder for myself as it helps me in the process of letting go. Letting go that I may not have all the design solutions. Letting go of harsh/trivial comments. As long it does not violate my values, morals and belief system — we’re good.

Here’s the twist though, you’ll never really be able to fully let go of your ego. It will always be there. It makes us who we are. It is not a bad thing. Just as everything in this world, too much of anything is never a good thing. So have a healthy dose of ego in moderation. What’s healthy you might ask? I am no expert, but an inflated ego has a way to make you seemingly rude and obnoxious towards others. Don’t belittle others. If you are aware of all these signs that makes up an unhealthy ego, you’re on to something. Be respectful and have some manners — that has always worked for me.

Article as featured on Foolproof.